The US, the world’s largest oil and gas producer, is headed for another year of record production, although with a significantly smaller increase as companies scale back activity following a wave of acquisitions in the industry, analysts have said.

Production from American oilfields reached a record high of 12.9 million barrels per day last year as companies utilised new technology to counterbalance lower oil prices and reduced rig counts.

Analysts and agencies expect modest growth in production this year, as the US rig count, considered an early indicator of future output, remains significantly lower than in previous years.

“The rig count declined throughout 2023, but the production impact will be felt in 2024,” said Utkarsh Gupta, senior analyst at Wood Mackenzie, an energy consultancy.

The oilfield services firm Baker Hughes reported that the US rig count declined by about 20 per cent last year after rising by 33 per cent in 2022 amid a drop in oil and gas prices, higher costs and rising focus on shareholder returns.

“High-growth privates have been acquired, and cost inflation prompted remaining small privates to cut rigs. Public [exploration and production companies] will continue to tow single-digit growth plans,” Mr Gupta said in a research note.

Wood Mackenzie has forecast a 270,000-bpd growth in output this year, which is close to the 260,000-bpd increase projected by the US Energy Information Administration, the statistical arm of the Department of Energy.

However, Macquarie analysts have adopted a more optimistic outlook on US production this year.

The research firm expects US supply to reach about 14 million bpd by the end of the year despite “industrial friction” from acquisitions and “subdued” growth forecasts from publicly listed companies.

“The shale landscape is not bereft of potential growth drivers in 2024, amidst ongoing cost deflation and the potential for counter-cyclical efficiency gains,” Macquarie said in a research note.

The challenges faced by the industry in the current year could potentially turn into tailwinds in the future, if private companies regain momentum and listed companies start to aggressively exploit high-quality resource areas in 2025, it added.

The US oil sector witnessed signifcant mergers and acquisitions last year as energy majors sought to enhance their presence in key domestic shale oilfields.

Exxon Mobil announced the acquisition of Pioneer Natural Resources in a deal valued at $59.5 billion. Meanwhile, Chevron agreed to acquire its smaller rival Hess in a $53 billion deal.

The main driver of the current surge in production is a delayed response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, which led to oil prices soaring to levels exceeding $100 per barrel for the first time in nearly a decade.

Roughly three quarters of American crude supply comes from its shale plays.

A shale resurgence, centred around the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico, turned the country into the world’s largest crude producer in 2018.

“We think US tight oil M&A consolidation will continue. Scale remains key in valuation multiples, and we expect companies to get larger,” said Nathan Nemeth, principal research analyst, lower 48 upstream at Wood Mackenzie.

Oil production in the US Lower 48 states, which excludes Alaska and Hawaii, will continue to increase gradually until the mid-2030s, but the rate of growth will be more subdued compared to previous years due to a combination of factors such as capital discipline, industry consolidation, and offsetting production declines, Mr Nemeth told The National.

While the increase in US production over the last two decades has helped address domestic fuel price volatility, it has also sparked concerns regarding greenhouse gas emissions, challenging America’s credibility on climate issues.

“Short-term guidance provided by some of the largest US onshore oil and gas companies shows significant production increases for 2024 compared to 2022,” Guy Prince, senior analyst at Carbon Tracker, told The National.

“Unless they switch from a production growth strategy, it’s hard to see how their overall production rates will come down within the next few years, despite the shorter duration of unconventional projects,” he said.

The US sanctioned the exploration of the highest volume of oil and gas reserves in 2022 and 2023, followed by Guyana and the UAE, according to a report from the Global Energy Monitor.

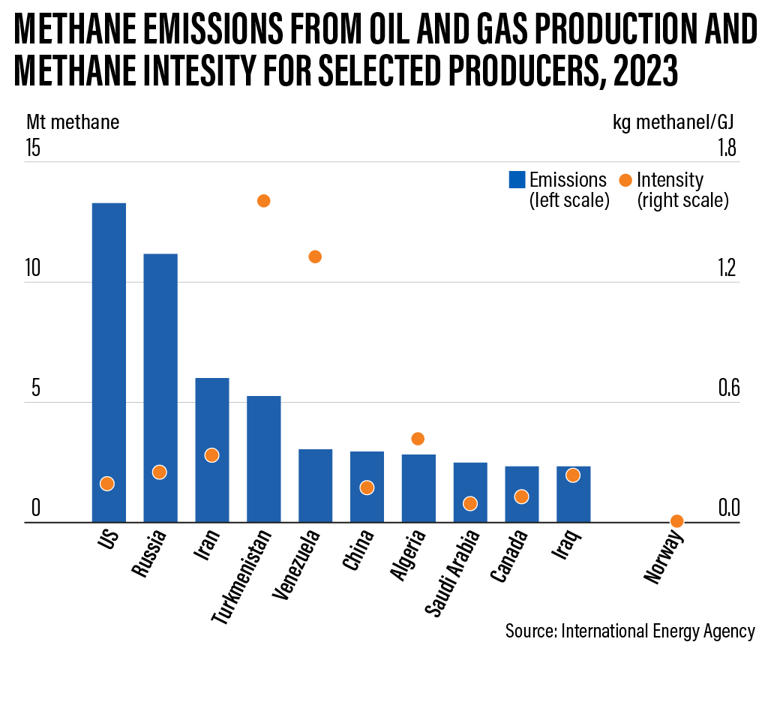

The country was also the largest emitter of methane from oil and gas operations last year, closely followed by Russia, according to the International Energy Agency.

This was despite actions taken by President Joe Biden’s administration to rein in fossil fuel-related emissions.

He terminated the Keystone XL Pipeline project, aimed at increasing the supply of Canadian crude to American refineries, halted the issuance of new liquefied natural gas export permits pending environmental assessment and reduced the federal oil leasing schedule.

The US Inflation Reduction Act, enacted in 2022, stands as the largest piece of federal legislation ever to address climate change. It offers a series of tax incentives for wind, solar, hydropower and other renewables, alongside a push towards electric vehicle ownership.

Meanwhile, former president Donald Trump has clinched the Republican presidential nomination. He has promised to prioritise boosting US oil and gas production if elected.

At the CERAweek energy summit in Houston last week, oil industry executives criticised Mr Biden’s policies but also expressed concerns that Trump returning to power could lead to increased volatility in international relations.

The US aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50 per cent to 52 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030, before becoming carbon-neutral by 2050.

Oil and gas companies worldwide have been investing in carbon capture, which involves capturing carbon dioxide from operations before emissions enter the atmosphere. It is then stored underground.

Investment by oil and gas companies into carbon capture, hydrogen and other abatement technologies may help, but many of these “lack demand, are too costly, and are not sufficiently scalable”, Mr Prince said.

The IEA has also warned against “excessive expectations and reliance” on carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS).

If oil and natural gas consumption were to evolve as projected under the current policy settings, this would require an “inconceivable” 32 billion tonnes of CCUS by 2050, including 23 billion tonnes through direct air capture, the agency said in a report last year.

It would also require $3.5 trillion in annual investments from today through to mid-century, an amount equal to the entire industry’s annual average revenue in recent years.